Blog: Sustainable funding in higher education

17 July 2017

Dr Tim Bradshaw, Acting Director of the Russell Group, blogs on the need for sustainable funding in higher education.

Sustainable funding for higher education

The UK has an enviable global reputation for its excellent higher education system and genuinely world-class universities, but that doesn’t come cheap: it needs proper funding and it needs a funding system that is sustainable over the long-term.

Sustainable funding for higher education has to work in three ways: for students, for universities and for the tax payer. Favouring one will ultimately lead to problems for the other two, so a delicate three-way balance has to be struck. How we keep the balance, and keep it fair, is something that should be kept under consideration and the current debate on student debt is a timely reminder of why.

For students, sustainability essentially equates to upfront affordability and an assessment of likely longer-term reward. There is plenty of data on the latter in terms of the salary premium associated with going to university [1], but often over looked (because they aren’t typically costed by economists) are the social, cultural and other wider benefits to individuals – a university experience really is much more than the sum of the time spent being taught.

It is right then that students should pay some contribution to their higher education to reflect this ‘private return’. The questions then become how much should students pay and is that affordable?

Our current funding model of capped tuition fees and government-backed student loans seeks to address the affordability question and keep the balance about right between students, the needs of universities and the tax payer. The fees and loans system isn’t perfect, but it has allowed more students than ever before to study at university [2] and in particular it has encouraged students from disadvantaged backgrounds to apply [3]. No student has to pay for their undergraduate tuition costs upfront and all can access at least some maintenance loan money, with more available to those who need it most. In addition, most universities – and certainly all Russell Group universities – have a range of bursaries and scholarship funds available so everyone with the potential, and the desire, should be able to find a place at a UK university. In other words, the system passes the affordability and long-term reward tests, at least in broad terms.

Our current funding model of capped tuition fees and government-backed student loans seeks to address the affordability question and keep the balance about right between students, the needs of universities and the tax payer. The fees and loans system isn’t perfect, but it has allowed more students than ever before to study at university [2] and in particular it has encouraged students from disadvantaged backgrounds to apply [3]. No student has to pay for their undergraduate tuition costs upfront and all can access at least some maintenance loan money, with more available to those who need it most. In addition, most universities – and certainly all Russell Group universities – have a range of bursaries and scholarship funds available so everyone with the potential, and the desire, should be able to find a place at a UK university. In other words, the system passes the affordability and long-term reward tests, at least in broad terms.

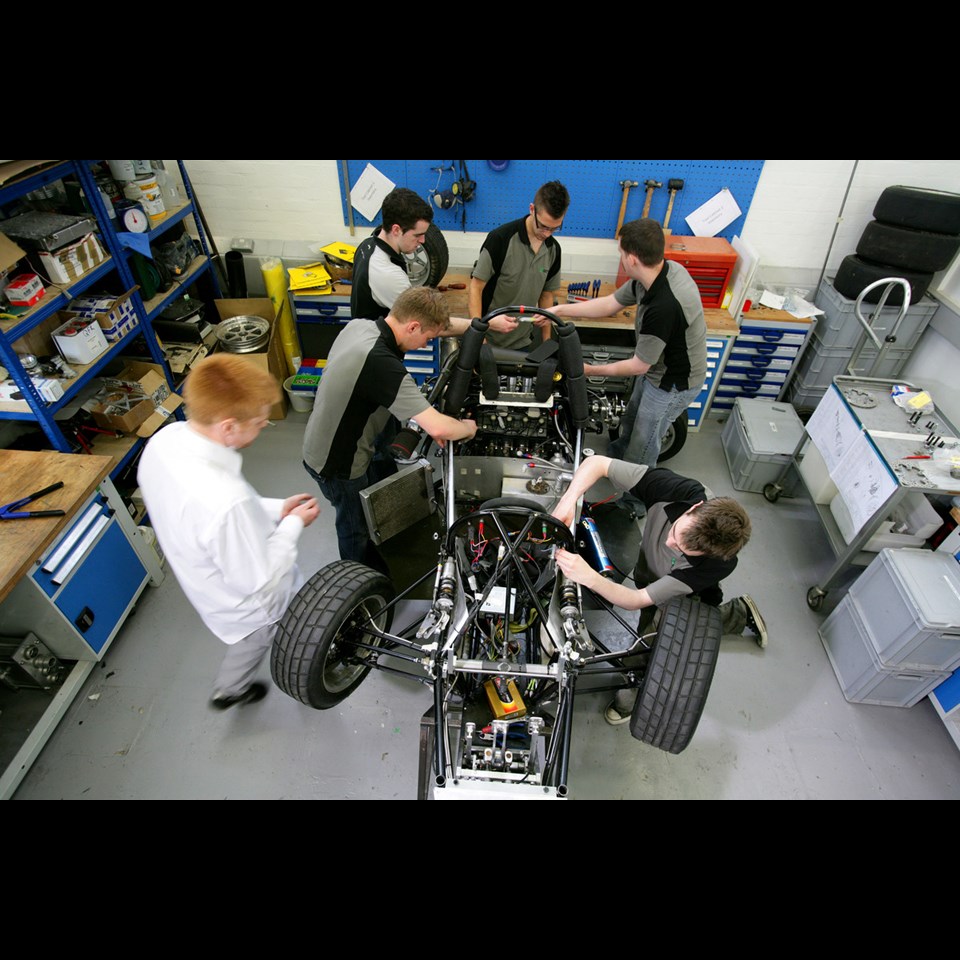

For universities, the income from tuition fees is critical to their overall sustainability. This income stream has replaced direct funding from Government (paid for by taxes). It means our universities are able to offer a diverse range of courses, high quality teaching and learning experiences, great facilities and opportunities for students to do everything from hands-on research to international placements and collaborative work with local communities and business. The system has provided a baseline of stability that has helped the HE sector become a key part of the UK economy – and for the Russell Group that means the ability to deliver high value jobs, growth and opportunity right across the country.

As the Institute for Fiscal Studies has pointed out [4], the loan system also works for the Government because it is regarded as ‘off balance sheet’ and doesn’t add to the deficit. It is complicated accounting, but remember the UK is still on the long road to recovery from the global financial crisis a decade ago and putting the bulk of tuition funding back on the balance sheet would almost certainly lead to much higher taxes and/or severe cuts elsewhere in public spending, such as in the health service, policing or defence.

The Government has also made a calculation in terms of the expected public return of a graduate education to the economy, which translates into how much of the student loans given out they expect to receive back in the future. At the moment that’s around 70%. In other words, the Government, or rather the tax payer, is willing to write off about 30% of the costs of degree-level education for the positive benefits this brings to the UK. (Actually, it is more than that as the Government also provides some funding to universities to cover at least part of the extra costs of teaching high cost subjects such as science, engineering and medicine.)

Crucially for students, this write-off means that debt repayments only start when earnings reach £21,000, while any remaining debts are cancelled after 30 years. You can’t get a mortgage or other loan with terms like that where the tax payer is taking such a high portion of the risk. It also means that mortgage lenders and others only look at monthly repayment amounts, not overall student loan levels, when they are lending to individuals – so having a student loan won’t stop you if you want to get a foot on the property ladder.

But I think we can still look again at how the system might be made fairer for students without undermining the sustainability balance. Three areas immediately come to mind:

- First, the interest rate on loans at up to 6.1% from this September (RPI + 3% for those on salaries of £41,000 or over) is out of touch with commercial lending rates, and very high compared with the rates at which the Government can borrow. A reassessment here now seems highly appropriate as inflation starts to return.

- The £21,000 repayment threshold could also be reconsidered. A higher level would allow new graduates to keep more of their earnings early on when individual finances are often tight. In 2015, the Government moved away from a previous commitment to uprate the repayment threshold in line with inflation. Many have argued reinstating the link could be of particular benefit to those students on low and middle incomes.

- Finally, how repayments are made could also be modified. Being able to make payments through salary sacrifice arrangements (which the Government typically supports for things like pension contributions) would reduce the tax bill for individuals and again help with their post-graduation finances.

Of course, there is a cost to Government finances for each of these suggestions, but ultimately this should be seen as an investment in the long-term sustainability of the UK’s higher education system and in the future of those who study hard for their degrees.

End notes:

- In 2016, working age (aged 16-64) graduates earned on average £9,500 more than non-graduates, while postgraduates earned on average £6,000 more than graduates. Graduate labour market statistics: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/graduate-labour-market-statistics-2016

- UCAS end of cycle report 2016 (page 42), Entry rates for 18 and 19 year olds from the UK: 18 year olds in England, Scotland, and Wales were more likely to enter higher education in the 2016 cycle than any previous year

- UCAS end of cycle report 2016 (page 79): Entry rates have increased across the period, with the largest proportional increase between 2006 and 2016 for MEM group 1 (most disadvantaged). For this group, the entry rate increased by 74 per cent proportionally. https://www.ucas.com/file/86541

- IFS, Higher Education Funding in England (page 11): The total government up-front expenditure for the 2017–18 cohort of entrants into HE is £17.0 billion. However, because 96% of this is provided in student loans, this expenditure only contributes £745 million to the government deficit (as loans provision is not included in the deficit until the loans are written off 30 years later). This is dramatically lower than for the 2011 system, in which £6.4 billion was paid out in grants and hence contributed to the deficit. This change is a result of the shifting of payments from grants to loans: replacing teaching grant funding with tuition fee loans in 2012 and replacing maintenance grants with loans in 2016. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/bns/BN211.pdf

-

Adam Clarke

adam.clarke@russellgroup.ac.uk

020 3816 1302

-

Adam Clarke

adam.clarke@russellgroup.ac.uk

020 3816 1302

X

X